Star Wars: Yoda Stories

PC - Lucasarts, 1997

When Yoda Stories was released, I wrote to PC Gamer UK asking for its’ due and was told "No dice, heretic." by John Walker one of my favourite games journalists who later went on to co-found Rock Paper Shotgun with the rest of my favourite games journalists.

Many years later in perhaps the 2010s as roguelikes became more popular I tried to garner some appreciation on that very website’s forums by enticing people with the promise of a graphical Star Wars roguelike. I was met with essentially "No dice, heretic." by the internet.

Third time’s a charm.

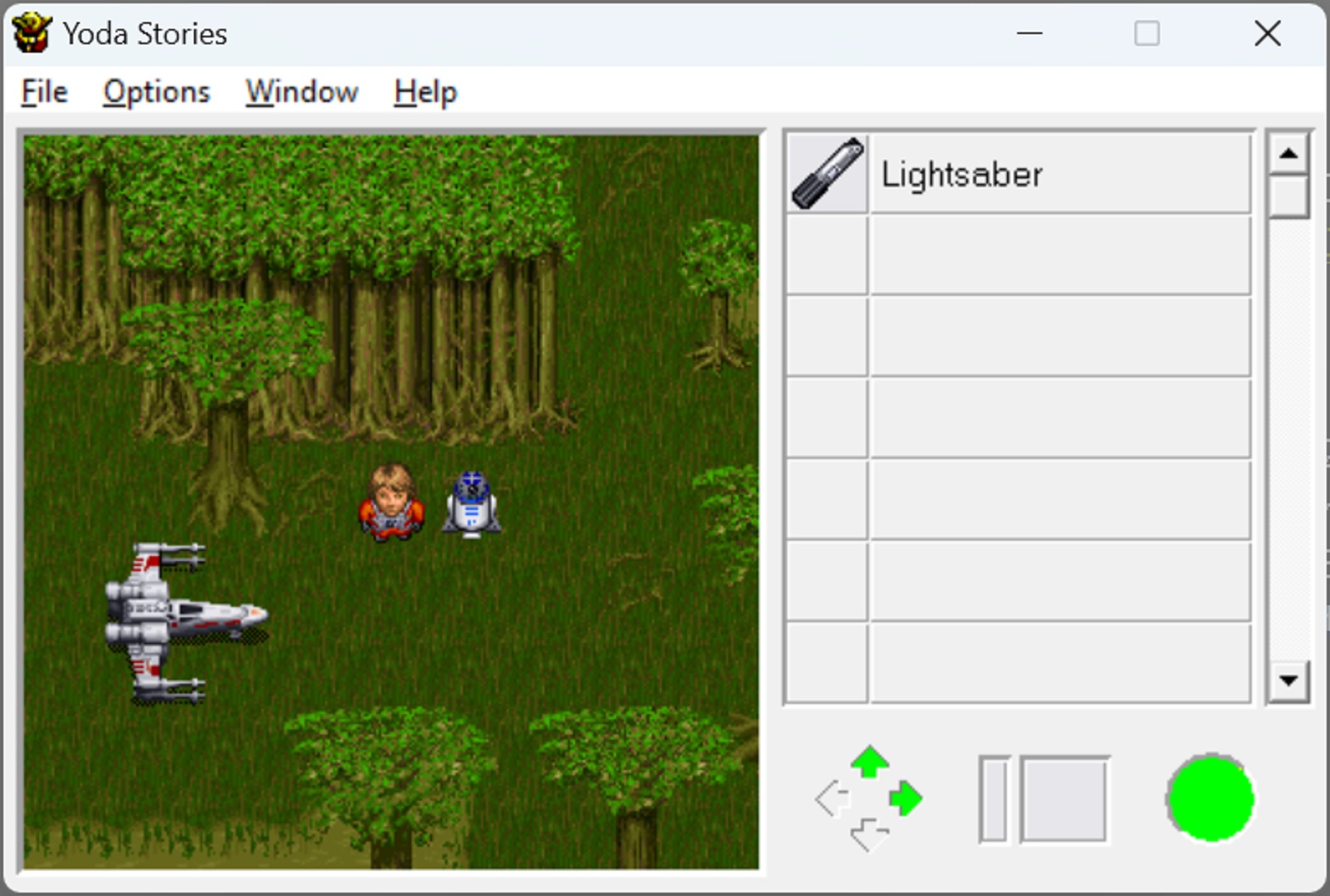

The sequel to Indiana Jones and his Desktop Adventures, Yoda Stories is a bit of a catchier title than Luke Skywalker’s Desktop Adventures, but the game remains largely the same as its predecessor. You are Luke Skywalker and you run around a procedurally generated planet on a variety of randomly chosen quests, puzzles and sub-plots while fighting off stormtroopers and other baddies.

We've covered the ins and outs in the Desktop Adventures review, but the main differences to the Indy adventure are a greater number of quests and a far more dynamic game generation. Sadly most of this is lost in the Game Boy Color version of the game, which had poorer graphics and a fraction of the content. It has the curious honour of being IGN’s lowest ever reviewed GBC game, and with good reason. The PC game is the version to play.

The Star Wars universe, even in the 90s, was a much richer seam to mine, and there were lots of familiar characters, vehicles, scenes and objects, as well as planets on which to fetch items for NPCs. You feel much more ensconced in the world, where Desktop Adventures felt like an Indy reskin of another game, which incidentally is exactly how it started life. Here, generic bandits and animals are replaced with stormtroopers, droids, banthas and the like.

Another innovation in this second outing is a feature that would become a roguelike stalwart in subsequent decades: permanent progression between games. Of a sort, anyway. Indy Quotient points are now Force Points and games are tracked. After certain numbers of games Luke will gain new particular weapons or powers, and even special missions and story scenes. However, the greatest leap in technology from the previous game is that with Luke's lightsaber you can now attack diagonally. This actually is more of a leap in quality of life than it sounds, making the combat slightly more bearable.

Just as with Indy’s adventure, I love the pixel art, or 'art' as it was called in those days. There is so much more of it for Yoda Stories, all of it instantly recognisable to any Star Wars fan even in its cute chibi style. In reviews of the time, the poor graphics seemed a particular bone of contention, at a time when consumers and critics alike were fiercely focused on graphics. This was the year of Goldeneye and watershed game Super Mario 64 for console gamers. Nvidia had just released the Riva 128 3D graphics card to go up against the 3dfx Voodoo and ATI’s Rage cards, for PC gamers with money to burn. Even Lucasarts itself would release Jedi Knight and X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter later this year, both of which were fully on board the 3D revolution.

Over the years, as development became more complex, creators moved to re-using or licensing existing game engines such as Quake, Unreal and now Unity, graphical advances became less important. On the PC, game creation again swung some way back towards the bedroom coders that started it. Indie games without the skills or budget for top end 3D graphics became popular. Nintendo gradually reinforced this trend, with their wildly popular Wii, Switch and handheld consoles, none of which were aimed towards high end graphics. As graphic advances plateaued, even AAA games in the 2020s compete on marketing bullet points other than graphics.

As a result, we’re much kinder to the 2D ‘pixel art’ of old, as we see much more of it today and it hasn’t aged compared to the early days of 3D (such as Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine). Even the pseudo-3D of Build Engine games such as Doom have aged better than their early polygonal successors. Camera and movement controls also took many years to standardise, which adds to the struggle of early 3D games.

There is something thrilling about coming across a little cartoon AT-AT, downed by a snowspeeder no doubt, or taking your lightsaber to a bantha, or coming across your favourite baddies while the Imperial March plays for a few short seconds. Quaint, perhaps, but strewn with the same playfulness Lucasarts was known for in it’s moe mainstream games.

Despite its detractors, die hard Yoda Stories fans were in good company. Zach Barth of Zachtronics (Spacechem, Eliza) did a technical teardown of Yoda Stories and found some interesting tidbits in the game files. Notable to me is that rather than procedurally generate the map squares as a modern game would likely do, instead the game constructs the game map out of over 600 different pre-made tiles.

Either way, it's replayable yet familiar and still has some surprises after many a game. Yes it can be frustrating, and somehow it had even lower review scores than Indy's Desktop Adventures despite being noticeably improved from the first game of it you play. But it's fun, and it's interesting as, if not a direct descendant, then at least a vestigial arm on the evolution of gaming, showing what could be for the much-loved roguelikes of tomorrow.

Both this and Desktop Adventures are fantastic little nostalgia that a handful of people have been playing for 30 years. With better controls and improvements to the formula, who knows what Star Wars: Roguelike One could have been like decades later. In the words of the creator Hal Barwood himself: "Too bad we didn’t make some more of these things.”