Trespasser

PC - Dreamworks Interactive, 1998

A mammoth(!) archaeological retrospective on Jurassic Park Trespasser and why it belongs firmly in the pantheon of gaming history. Digging up its legacy, its contemporaries, faults and successes, and why the developers were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should.

QuickLinks

Teamwork Makes the DreamworksStorytelling

Ambitious Design

Graphics and Animation

Let’s Get Physical

The Arm

The Chest

The AI

Other Ambitions

Welcome to Jurassic Park(‘s Backup Site)

Survival of the Fittest

Playing Trespasser Today

Hammond’s Legacy

Teamwork Makes the Dreamworks

In 1994, Steven Spielberg set up Dreamworks movie production company in order to branch out into new genres as well as animated feature films. 1995 saw the release of the Sony Playstation, with the Nintendo 64 not far behind, ushering in a new generation of gaming and showing creatives and publishers what games were capable of. An avid gamer, Spielberg set up Dreamworks Interactive, a joint venture with Microsoft with a big ambition to further what video games could do.

In 1998 Dreamworks movie arm was in full swing with two Oscar nominations under their belt, but the developer was not doing so great. A New York Times article at the time notes that Dreamworks' critically acclaimed claymation adventure game The Neverhood (1996) sold 37,000 copies (I was one of those!), meanwhile even games such as Barbie Fashion Designer sold 400,000, in a decade when gaming was mostly geared around a male demographic.

But Spielberg had big ambitions for Dreamworks' games division, and they have made their mark on history. Aside from The Neverhood they would go on to create Spielberg’s Medal of Honour franchise which would in turn directly inspire Call of Duty, the biggest-selling game franchise of all time.

Thanks to the Spielberg connection, Dreamworks also developed Jurassic Park games Chaos Island: The Lost World and The Lost World: Jurassic Park alongside the movie in 1997. In 1998, after 3 years of development and to a huge amount of hype and fanfare, came another Jurassic Park game: Trespasser.

It bombed. Trespasser immediately received terrible reviews and a decent amount of mockery, selling a mere 50,000 copies (I was one of those as well!). Interestingly, it lost out to Gamespot’s Most Disappointing Game of the Year Award 1998 to Star Wars: Rebellion. Trespasser has a special place in my heart and Rebellion (known as Supremacy in the UK) is probably the game I’ve played most over the past 25 years, so perhaps Gamespot is not for me.

Even at the time, there was no denying Trespasser was a product of the serious ambition of Dreamworks and Spielberg. Over the years it has developed an appreciation and a perhaps cult following, although many online reviewers still use it for low-effort derision for YouTube videos and such. Not to say it doesn’t deserve the jibes, but Trespasser did a lot to push the envelope of games as we know them today.

Storytelling

First of all, and I think first on Dreamworks’ priorities as well, was the storytelling. Immersing the player in the story experience is repeatedly referenced in interviews with the development team and it's part of the raison d'etre of Dreamworks. The team was given ‘near total’ creative freedom by Universal, and they used this to tell a new and engaging story. Richard Attenborough returned as John Hammond, and Minnie Driver provided the voice of the main character, Anne. They spared no expense.

At the beginning the player is treated to a cut scene with Attenborough filling in anyone who hasn't seen The Lost World. Anne's plane crashes on Isla Sorna, the island location of Jurassic Park's back-of-house, Site B. The first area plays out as an in-game tutorial, something usually credited to Half-Life (1998) as popularising, and Anne soon learns where she is and what an adventure she is likely to be in for.

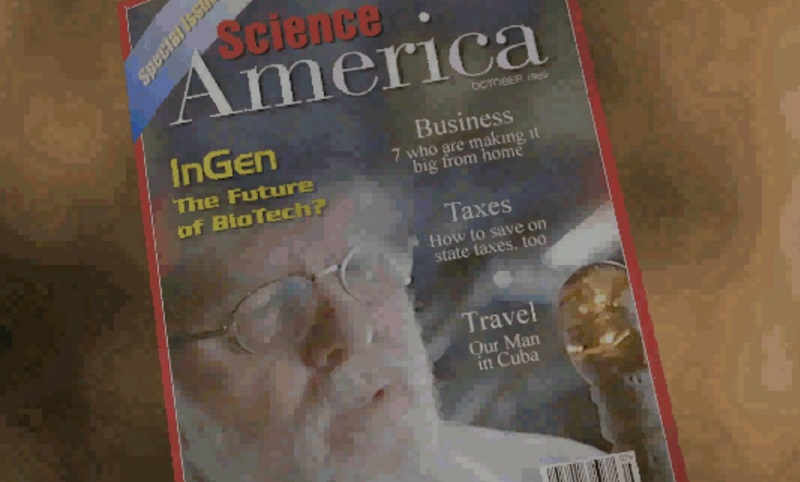

Austin Grossman worked on some heavy-hitter PC games like Deus Ex and Dishonored. Just like the executive producer of Trespasser, Grossman got his start at the legendary Looking Glass Studios on System Shock, where he pioneered storytelling via audio logs, a mainstay of video gaming 30 years later. In Trespasser they are not just story dressing, but the only real element of explicit storytelling in the game. Anne talks to herself occasionally, adding colour to the story and helping the player understand what's happening and what their next objective might be. Attenborough in particular gives a wonderful performance, and exploring the environment while he reads excerpts of Hammond's memoirs feels very dream-like rather than hearing an audio log. It fills in a lot of backstory behind Jurassic Park and adds some context to Site B as you explore it.

Ambitious Design

The decision was made not to include any NPCs in the world, as unrealistic looking humans may break immersion, so the audio memoirs were supported by environmental storytelling. Most of the game is spent in discovery and exploration, as well as some basic puzzling and awkward shooting. An internal leaked developer walkthrough gives us some idea of the approach the team were taking. There are two particularly telling quotes:

"Your first objects: Some objects lie on the beach for the inquisitive player to pick up and start toying with"

"Awesome view: The player can climb the concrete blocks to get an awe-inspiring view over the jungle trees."

They wanted the player to have agency and experiment. The inclusion of a nice view that could only be seen if you were curious enough to climb the tower and have a look instead of go charging into the forest shows you the philosophy of the design. Entries often begin with phrases like ‘If Anne doesnt know how to do x, she can do y’ or ‘If Anne goes east instead of west, this should happen’. All of this points towards the immersive sim genre. In fact, in an interview before the game was released, Dreamworks game designer Richard Wyckoff was calling it "Jurassic Shock", comparing it to System Shock on which many of the team worked. You won't find Trespasser on a list of immersive sims today, and the shipped product only scratches the surface of the genre, but the attempt is clear.

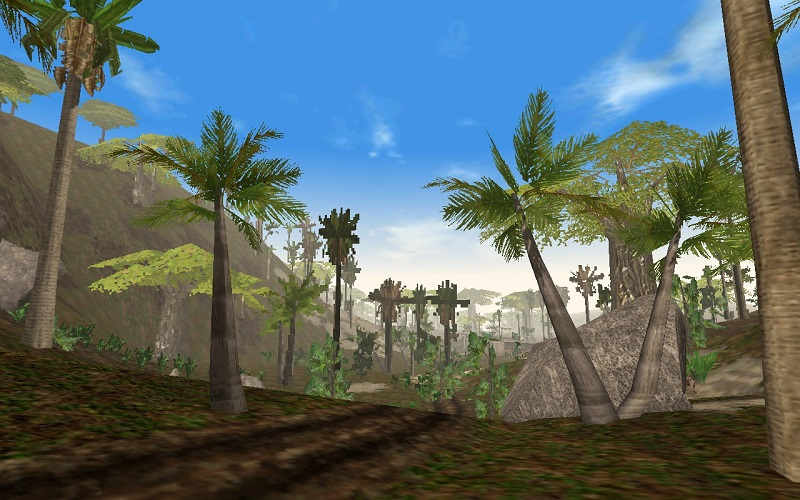

The ambition extended to the world itself. Isla Sorna is based on a laser scanned physical model of the island, on which were placed 10-15,000 trees, rocks and other objects per level to give the feeling of wilderness. The goal was a fully open world game but the technology did not exist to realise this. The game is broken up into large open levels, and free-form exploration of the whole island was ditched in favour of a more traditional linear structure between them.

Executive producer Seamus Blackley has a positive outlook on the lessons learned from Trespasser and often speaks candidly about it. In his interview with trescom.org he notes that there was no standard process for creating a huge believable world from scratch, let alone adding in the rest of the ambitious elements the team were aiming for, so they made it up as they went along.

A mere six months after Trespasser was released, Richard Wyckoff published a brutally honest post-mortem on gamedeveloper.com while the feelings were still raw. This was less positive than his pre-release interview, and was scathing about many aspects of development, the lack of design structure was one of them. The previously mentioned, and rather informal, leaked developer walkthrough was said to be one of the only design documents in the project, which contributed to overreach. Ultimately this lack of focus, which Wyckoff blames on poor management, meant feature creep, budget overrun and missed deadlines. When the studio handed them a final deadline to meet the VHS release of The Lost World, the team slashed features everywhere, leaving a lot of disappointed fans in their wake.

Graphics and Animation

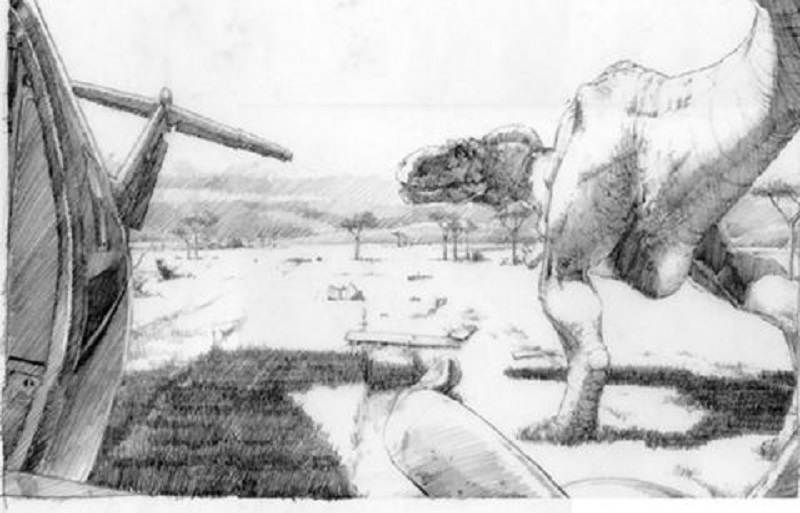

The late 90s was still the realm of the ‘corridor shooter’, first-person games which were mostly indoor environments with linear progression. Trespasser’s move to a huge outdoor island presented graphical and performance challenges to the developers.

The graphics were already pushing the envelope for the time, without even taking into account the large draw distance and amount of level furniture needed to present a convincing tropical island. It was also one of the few games that used a technique called bump mapping, not popularised until Doom 3 (2004) six years later.

To make realistic dinosaurs they not only needed the highest quality of 3d models and textures, but also animations. In fact one of the driving forces behind a dinosaur, and therefore Jurassic Park, game was a desire to make use of the biped animation system Blackley had been working on for a previous Looking Glass release Terra Nova: Strike Force Centauri (of which I wore my demo disc to the bone as a kid). This inverse kinematics system would mean a more realistically responsive movement to the dinosaurs when walking over terrain, being hit by bullets or objects and so on.

This all sounds great, so what went wrong? Unfortunately the animations speak for themselves, and lead 3d artist Brian Moore would lament that pre-animated dinosaurs would have looked much better, with artists doing the animation, rather than programmers.

On the graphics side, it was again too ambitious. A huge amount of work went into the bespoke 3D engine to cope with the vast, densely populated levels, but even the best PCs of 1998 could barely cope. The draw distance was lowered, and objects popped from 2D to 3D as the player approached. To further improve performance, dinosaurs would also remain static, only springing into life as the player got close enough to them. Worse still, the first 3D graphics cards came out towards the end of development. The team began to try and integrate the technology so the game could run on the new cards like the 3dfx Voodoo, but much of their engine didn't work on it. The result was a hodgepodge of 3D models mixed with their 2d sprite replacement system for objects in the distance, and a game that ran poorly on anything.

Let’s Get Physical

The invention of physics-based puzzling is often attributed to Half-Life 2 (2004) but it’s now more widely appreciated that Trespasser takes that crown 6 years earlier. In fact, Gabe Newell himself admits he was inspired by Trespasser when making Half-Life 2. The trend of realistic physics engines caught on with the release of Havok Physics, a middleware that could be purchased and integrated into games. It was Havok which was used in Half-Life 2 along with countless other games, the first of which wasn’t released until two years after Trespasser. Another title taken is that of first game with ragdoll physics, although the implementation mostly makes raptors bob around after death, like a child’s inflatable punchbag.

The team even created a new audio system to cope with the physics objects and how they might interact. Again they were breaking new ground. Another quote from the leaked dev walkthrough mentions a potential physics puzzle "This is one of those puzzles we'll just have to try out to see if it works."

Inventing new types of puzzles using a physics engine needs a lot of testing, which is time and money they didn't have. When cutting features to meet their final release date, one of the biggest casualties was nearly every environmental physics puzzle, for which they had high hopes. They were left with a repetition of less impressive set piece puzzles like stacking boxes and making bridges.

The Arm

Aside from the puzzling there is shooting, and it’s not a high point. There is a charm to it, and you can only carry two weapons, not a whole inventory’s worth as with other games. Halo (2001) will later be credited for popularising the two weapon limitation. And it's not just weapons, there’s no inventory at all, you carry what you can hold. So if you need to pick something up or press a button, you need to drop what you’re holding. This sometimes leads to some silly situations as you throw items or guns around, not wanting to leave an item behind, and physics bugs will occasionally make you drop something without you noticing. There’s no reloading either, so pick up a new gun and you’re dropping precious ammo remaining in the old one. The gunplay is more like Receiver (2012) a slow-paced FPS that is focused around the detailed processes around using a weapon, with manual reloading, chambering and so on. Unfortunately it’s not meant to be, it’s just a constant battle to use and aim the guns with your arm.

Ah yes, the arm. A favourite of professional content creators everywhere as it’s so obviously ridiculous. I’m not sure why the decision was made to continue with this in development, in favour of at least a toned-down version. To control your arm you hold a button while using the mouse to position your arm, or hold two other buttons for rotating the arm or wrist. Once you release the button, the arm stays in that position, moving with you as you look around. This means you can't look around and move your arm at the same time, so you must remember to position your arm forwards with a gun ready if you’re expecting enemies. Wait until trouble arrives and you won't be able to control your unruly appendage in a panic. Despite what the detractors would say, in practice this becomes second nature after a while so you can essentially aim and fire like a normal FPS. It does look silly and get in the way occasionally, but it generally only flails and contorts wildly if you make it.

Mercifully, Anne’s left arm was broken in the plane crash because the developers couldn’t get her other arm working well enough. I am more forgiving than most about the arm, but even I admit two of these nightmare arms would have earned a ‘psychological horror’ tag on Steam.

But even the arm has a lasting legacy aside from the glut of articles bashing the game. Two games have openly declared their inspiration from the arm, Octodad (2010) and Surgeon Simulator (2013). Unfortunately, both provide their entertainment via how comical it is to control a game in this way but hey, it’s some kind of legacy.

The Chest

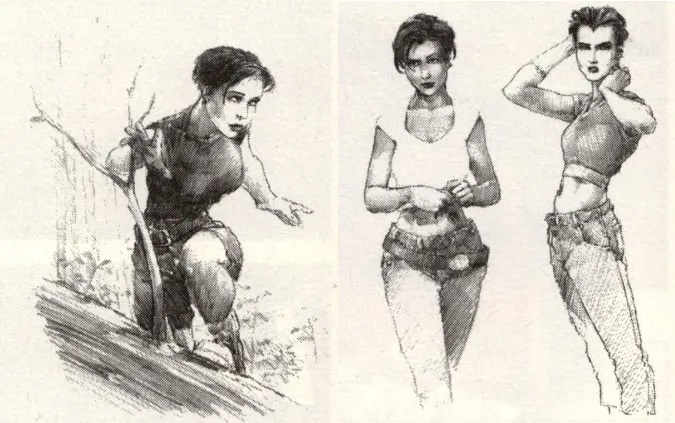

Apart from the arm there is also a set of 3D modelled breasts which we will need to discuss in some detail. The decision to have a female protagonist was made before Tomb Raider (1996), the team wanting everything to set it apart from its peers including the gender of the main character. Unfortunately for them, Lara Croft stole Anne’s thunder during the protracted development.

Without a traditional user interface, you must look at your cleavage in order to see your health, which is represented as a heart tattoo which turns red as you lose health. Why were there breasts in the first place? There is a long and proud history of being able to see your legs in video games, including Duke Nukem (1996).

Trespasser, though, is not one of them. There was the intention to see your body and have legs that interacted with the world and the physics and animation systems, however they didn’t work. The leg models were removed and so, as we can tell from a pre-release prototype, in order to hide the missing legs from the player the chest size was increased. Allegedly the heart tattoo was only placed on the chest until the arm was fully functioning and finished, which there wasn’t time to do before the rushed release. The chest was a product of circumstance rather than a cynical bid for the target young male gamer demographic.

It could be an excuse for something that hasn’t aged well, but it does track with what we know and can see from the game and previous builds. I give them the benefit of the doubt given their pedigree and the desire to have a female lead who is intelligent and capable. I can’t see Spielberg giggling like a schoolboy at the tattoo.

Still, even on the arm it’s a weird choice that unfortunately took a lot of focus away from the good parts of the game. For something that tried to focus so much on simulation, it's odd to have this magical tattoo break your immersion in such a fundamental way. In practice it doesn’t matter much as you won’t be looking at your cleavage often. Either dinos kill you quite quickly, or you kill them and your health regenerates, so despite the fuss made about it, you never actually need to check your health.

The AI

The goal for the dinosaurs was for them to be part of the ecosystem, interacting with the world and the game systems just as you were. The team developed a complex system of behaviours and emotions that would allow the dinos to act and react like wild animals. This worked to an extent, and you may experience some emergent behaviour and events thanks to the less scripted AI. If you can tempt one carnivore near another, it may kill it for you, or you might stumble upon a dino fight and sneak by while they’re occupied.

Not only were these systems not ready for release, some dinosaurs were not even in the game until a few months from the deadline. This was yet another new system that needed a huge amount of testing and iteration to perfect, and they didn’t have the time. Some behaviours were dropped, along with pathfinding within buildings, so the dinos were now restricted to outdoors. The complex emotional AI system was cut in favour of leaving the dinos perpetually in the ‘angry’ state.

In his post-mortem, Wyckoff points out that they ended up with the very same lifeless AI monsters from other games that they were trying to improve upon.

Meanwhile Half-Life was released in the same year, and its monster AI blew Trespasser out of the water. In the year Gamespot named Trespasser one of the most disappointing games of the year, they called Half-Life’s AI "frighteningly realistic".

Other Ambitions

Ambition was sky high in almost every aspect of the game. The total lack of UI was novel, with the aforementioned tattoo supplemented with the main character providing helpful information in lieu of a HUD. She will tell you what’s going on, how many bullets are left in the gun and so on, which I actually rather like. Diegetic interfaces were lauded in many later games such as Metro (2010) which shows ammo on weapon readouts and similar, something which is now commonplace.

Many other games such as Halo and Fallout 3 (2008) use partially or fully diegetic interfaces as well to great effect. Using in-game keypads and buttons, even physically opening doors like in Amnesia: Dark Descent (2010) can really immerse the player in the world. It just turns out that you don’t need to model a human arm to manipulate, doing these things with the cursor is a better solution.

Regenerating health is another mechanic that was not usual for this genre of game in 1998. Halo popularised regenerating shields in 2001, but Trespasser got there first. Again it breaks with convention, although is regenerating health any more realistic than picking up a first aid kit?

The background noises of the wilderness are great, but even the audio couldn’t just be standard. The soundtrack is an original work by Bill Brown, the movie soundtrack being too expensive to licence. The goal was for dynamic music, reacting to what’s on the screen, but again it fell short. The music kicks in at specific points triggered by the developers to coincide with set pieces, not adapting to what is happening to the player. While the music is good and very appropriate to the movies, most of the time there is no background music, just the sounds of the rainforest. To me adds to the tension and feeling of isolation, like in the original Tomb Raider.

Welcome to Jurassic Park(‘s Backup Site)

The first time you see a dino was always going to be a big moment in the game. Sure they are a bit wonky, let's be honest, but it does try to capture the majesty of the similar moment in the first film with the perspective and music. Your choices of path will decide whether you see the first gentle giants from the top of a mountain or from ground level, both being equally impressive. That’s classic immersive sim design. The first time you see a T. rex has a similar feeling, a mix of fear of a huge enemy and forgiveness for old gaming technology. It has less of an impact if you’ve met the T. rex in Tomb Raider two years earlier, who to be fair also looks quite goofy but is an altogether better T. rex experience, especially for a game not all about dinosaurs.

The levels are each quite memorable to me, some more than others but care was taken to make sure the player isn’t just moving along identical jungle corridors. Each has its own theme or novelty so that it differs from the others, in appearance and experience. At around 8-10 hours there isn’t much filler, although that may be more to do with the rushed deadline than a design choice, as much of the leaked cut content may indicate. You will be freely exploring a town in one level, following a dangerous path in another, with lots of verticality and variation.

As is made clear in the opening movie, you’re visiting some familiar places. I wouldn’t say Site B’s town and Ops Centre is high on the list of classic film locations but it’s fun to visit somewhere you’ve seen on the big screen. They’re recognisable but, as there are so many buildings in the town level, the detail is low. Compare this to Goldeneye (1997), which focused on smaller scale and interior locations from the movie with a much greater level of detail, it was amazing feeling like you were on the movie set. Putting the player inside the movie wasn’t the expressed goal of Trespasser and it has a good sense of place, just not a good sense of being in the movie.

There are other familiar locations though. I remember first reading Kieron Gillen’s review of Deus Ex (2000) and being wowed by him shooting hoops in what was not yet called an immersive sim. I’ve shot many a hoop on that Hell’s Kitchen basketball court as well as many others since then, but I didn’t realise at the time that this was somewhat of a trademark featuring in other games made by former members of Looking Glass. If nothing else convinces you that Trespasser is an immersive sim, then maybe this will.

What it won't convince you of is that realistic physics makes for a good basketball game. It’s almost impossible to score a basket in Trespasser, much easier and more enjoyable in the other Looking Glass games and their descendants, which focus more on fun than physics. A microcosm of the wider game, perhaps.

Survival of the Fittest

1998 was a big year for games and Trespasser couldn’t live up to the competition. Tomb Raider beat the team to having the first dinosaur-fighting female protagonist, and its 1998 sequel was bigger and more bombastic. Players were wowed by the convincing AI and environmental storytelling of Half Life. As an immersive sim with emergent behaviour, 1998 will be remembered for Thief, not Trespasser. And for the lofty goal of introducing a new genre and concept to video gaming, Battlezone was a successful and inventive blend of FPS and Real Time Strategy. Grim Fandango also made use of Lucasarts’ existing iMUSE system to provide dynamic music, beating Trespasser on yet another of its goals.

Even looking to consoles, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (N64) made a stronger nod in the direction of open worlds, another item cut from Trespasser’s wish list. Worse still for Dreamworks, Turok 2: Seeds of Evil wouldn’t come to PC until the following year, but in 1998 the dinosaur shooter was being praised on N64 for its advanced graphics and open ended levels.

None of those games tried to do everything, just excel at something. Every one of those games was more successful than Trespasser, and some are still considered the biggest names in gaming history.

Playing Trespasser Today

Flawed games always seem to foster close-knit communities that endure for decades on some archaic 90s website or forum. Some of my favourite games from my youth like Hardwar (1996) and Jagged Alliance 2 (1999), and Gamespot's big disappointment Star Wars: Rebellion had small groups of people keeping the game alive for years out of pure passion, until the inevitable remakes or re-releases provide official support and interest. Trespasser is no different, with ongoing community mods, remakes and patches from a group of hardcore fans centering around TresCom.org. As of 2023 there are many mods and upgrades, the latest fan created update is the CE patch which fixes a lot of issues without changing too much from the vanilla game. Having played the original many times, this patch is a great way to start off.

But should you give it a go? It’s around 8-10 hours long, and if you remember it from the 90s then it’s a fun nostalgia trip. If you have an interest in immersive sims then you should also definitely give it a go. Fans of Jurassic Park will really enjoy John Hammond’s story alone (although you can find the text or audio logs on the Jurassic Time website). If you’re none of those things it’s still a piece of gaming history to experience, and if you are willing to look past its flaws I’m sure you will find something to enjoy.

Hammond’s Legacy

In his post-mortem, Wyckoff compares the development of Trespasser to Hammond’s hubris leading to the failure of Jurassic Park itself, and it’s a fair comparison.

As we’ve seen, it inspired Half Life 2, a landmark for video games. John Carmack also cites Trespasser as an inspiration for Doom 3, and it’s also been referenced for Far Cry’s (2004) open jungle world. Director Peter Jackson and famous game designer Michael Ancel were inspired for the King Kong (2005) game of the movie. Bill Gates was so impressed with the technology on Trespasser that he hired Blackley, who went on to create the Xbox. Sometimes it pays to have high ambitions. Spielberg himself appreciated what Trespasser attempted, and approached Blackley to create a new sequel in 2012. Though it never materialised, Blackley’s concept allegedly went on to become the 6+ billion dollar movie franchise Jurassic World. That’s certainly a legacy.

Billed as a ‘digital sequel’, at least as much effort went into integrating Trespasser with the Jurassic Park canon as Shadows of the Empire multimedia project was to the Star Wars movies. With Shadows released in 1996, and Spielberg being a close friend of George Lucas, I wonder if Trespasser was a reaction to that unique proposition.

But it was so ambitious. Even if you ignore that the game was unfinished, so much was breaking the mould that there was nothing familiar left for the player to hang on to. That so many aspects of the game are standard in the industry 20 years later might explain the fondness, as more people rediscover it. But in 1998, unless the player was prepared for something very new and alien, they were always going to bounce off.

In the words of Seamus Blackley "It felt like the future, and I felt like we were ready to take it on. And it nearly worked."

All game posts:

© P7uen 2023 | Base style css by EGGRAMEN 2020