Star Wars: DroidWorks (1998)

PC - Lucas Learning, 1998

As gaming rose to prominence in the 1990s, many companies ventured into 'edutainment' games, keen to move away from simple learning software and engage kids at an early age. Brands like Tonka and Lego were breaking into the burgeoning market, with toymaker Mattel buying software house The Learning Company in 1998. George Lucas had dissolved his previous attempt at a learning company in the 1980s, but decided to try again in 1996 with a spin off from LucasArts, Lucas Learning.

Despite being tarnished with an ‘edutainment’ brush, DroidWorks’ core experience is a build-and-test gameplay loop which created a genre for such giants as Kerbal Space Program (2011). Building your own robots and taking them through challenges in 3D levels is great fun, and the educational aspect is incredibly well integrated.

Fan favourite The Incredible Machine (1993) is often considered the original contraption building game, but the similar, more technical Invention Studio (1996) was an inspiration for DroidWorks. Both of those games are relatively linear and restrictive; while they gave you specific puzzle pieces put in the right places, DroidWorks and its descendents give you the whole Lego box and it’s up to the player to use it wisely.

If you were being generous (and slightly sadistic) you could put Star Trek: Starship Creator (2000) on the list, but the other hit of the genre was popular freeware physics game Bridge Builder (2000) which had many sequels and inspired many clones that are still being made today such as the Bridge Constructor (2011) and Poly Bridge (2016) series’. Other modern entries in the lineage like Beseige (2020) and Main Assembly (2021) follow the same structure: build your bridge/spaceship/robot/medieval torture vehicle from a selection of parts. Switch to test mode and, with trial and error, hone your designs to complete your mission.

Through the 90s most physics and puzzle games were a string of unrelated puzzles and although George Lucas took some convincing, DroidWorks included a storyline tying the missions together. You are an agent of the Rebellion tasked with finding an Imperial droid factory and reprogramming the army of assassin droids being built.

But before you can tackle your missions, you need to design your droids. Handily, the Imperial factory is located on Tatooine, home of the Jawas, whose spies are part of the Rebellion. They let you use their sandcrawler and all the droid parts they have scavenged so, posed as a Jawa, off you go to build droids to help you in your quest. This is possibly a bit fast and loose with Star Wars canon, but as project leader Collette Michaud light-heartedly noted in a GDC presentation, "The great thing about classic Star Wars is they don't care about it! They care about Episode 1." They had much more leeway with the characters and universe during the late 90s, when Lucas was more focused on the prequel trilogy.

Pieces easily snap together very simply, with colour-coded snap points for a set of legs, body, head, one or two indiviual arms and the hands to go with them, and as much battery power you can carry. There is no freeform placement of parts (something that was cut during development), simply choose your parts and pop them on your droid. Everything is infused with some opportunity for learning: some are heavier than others, some parts are magnetic, you can have a pushing or grasping robot hands, tank tracks, wheels or legs, night vision, even a vocoder for speaking to characters in the levels. Best of all, each head has a different personality, voice and dialogue options within the missions, which is even more reason to experiment with designs and replay the levels.

In total there are 87 droid parts and may have been more, as in a game post-mortem Michaud notes “At one point during development, we could build over 65 million fully functioning droids, but design decisions forced us to cut it back to 'only' 25 million.” In reality this type of claim often results in millions of very similar end products, but there are a pleasing variety of looking and functioning droids to be had here, especially with the ability to paint two or three different colours on each part.

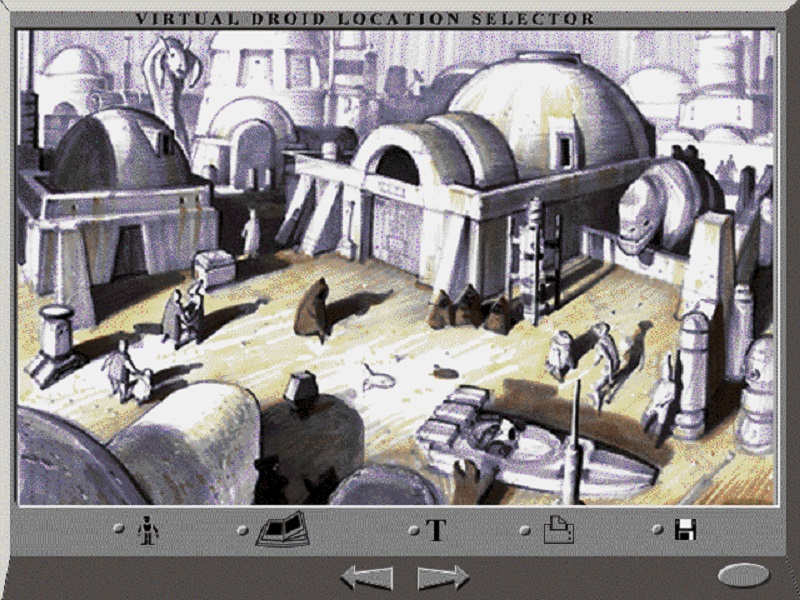

Of course, I spent many hours simply designing droids and ignoring the missions. You can recreate your favourite droids from the movies and games, mix and match or create entirely new ones. Your droids can be saved and loaded for posterity or so that you can use or alter them for use in later levels. The designer screen is in full 3D, with the ability to zoom and rotate your creation using the buttons on the screen. A named influence on the droid screen was Barbie Fashion Designer (1996) which, despite 3D graphics still being in their infancy, showed you a 3D animation of the clothes you made in the 2D designer mode.

There is a nod to another inspiration here as well, Mighty Math: Cosmic Geometry (1996) and its (much more limited) robot designing minigame. At the bottom of the screen a music button plays funky music, complete with a little graphic equaliser, and starts your droid dancing to the tune. All droids have a different dance, a combination of the animations on their various parts. I guarantee you will click the button every time you've finished your latest droid for a quick robo-boogie. But while the goal of Cosmic Geometry's minigame was the dancing, that is only the beginning for DroidWorks.

You can test your droid out in the training area against many of the obstacles you will encounter in the levels, but sooner or later you will start the initial eight missions, each of which has three increasingly difficult challenges to complete that will require tweaking of your design. This is a common feature of modern games, but by replaying the level with added challenges you can attain ranks of 'Apprentice', 'Designer' and 'Master'.

Each level is introduced with a cut-scene (short ones, as the team had clear direction that "George hates cut-scenes!") voiced by your Jawa friend, and they are pleasingly varied. The game introduces puzzles and concepts individually, and gradually combines what you’ve learned to get you thinking. You are given freedom to do any of these missions in whichever order you please and success unlocks more droid parts for you to play with, as well as four hidden story missions. The final mission to reprogram the evil droids uses many of the lessons you’ve learned in one big finale. No spoilers here as usual, but the finale is hilarious, the ending to the game being classic LucasArts humour. Also a LucasArts hallmark is the high production values and attention to detail including the finale's secret Rebel code spelled out in correct Aurebesh (I checked!).

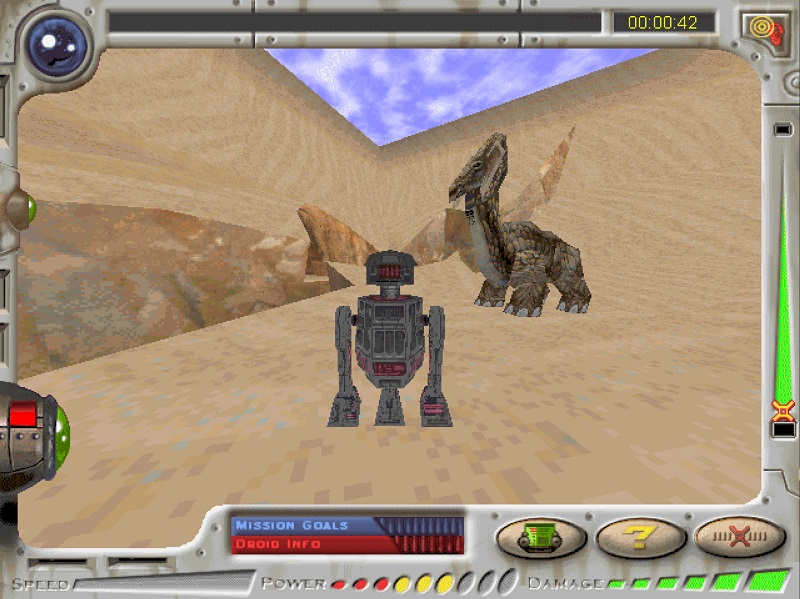

DroidWorks was designed for 9-12 year olds and marketed to age 10 and above. I was 15 at the time and hungry for Star Wars, but 25 years later and the missions are still fun and interesting thanks to solid game design principles not condescending to children. Michaud notes the environmental puzzles were inspired by games like Tomb Raider (1996) just made more explicit, and specific, making droid design the key to completing the missions. The puzzles are designed such that many different droids designs or parts can complete them. Simple concepts used for completing levels include counterweights, pulleys, magnets, levers and fulcrums, gears, angles, logic puzzles, power and so on. Some levels can be a bit long, but it’s aged quite well apart from the slightly clunky (maclunky?) feeling of all early 3D games.

Jawas and locals to talk to or give you hints, but the main enemy is the assassin droid. Occasionally one appears to chase you around the level, yelling at you. With no way to defend yourself, you just run and hide. It’s not quite Alien Isolation (2014) but it's scary for kid and a good bit of fun. A core tenet of the design was that there be no violence, no guns or explosions, and that the player would use their brains, not their reactions, to succeed. This no violence promise means the droid design and your brain are genuinely your only weapons. Rather than blast everyone and get to the end, missions are often to help other droids or local people, fixing broken things and so on, all very positive.

New droid friend Holocam E a.k.a. 'Cammy' guides you and acts as the player camera just like Lakitu in Super Mario 64 (1996), alongside R2-D2 and C-3PO. Threepio is voiced by Tom Kane who does voice work in every Star Wars game you’ve ever played. He's a fine C-3PO if you squint your ears, but not as good as Tony Pope who voice goldenrod in one of my favourite games of all time Star Wars: Rebellion (1998) among others.

The 3D engine used for the missions was the Sith engine, built for Star Wars Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II (1997). As a sister company of LucasArts, the development team were able to have access to the engine and all the development skill and resources that went along with it, saving them a lot of time building their own 3D engine from scratch. The trouble was that Jedi Knight's physics were 'game' physics, suitable for a fast and fun FPS game, but not suited to representing real-life physics to the players. A lot of the engine had to be rewritten, added to or adapted, and many situations scripted. In the end this may have been just as much work as creating a simple engine for the purpose. It also meant that a lot of the levels and puzzles that the team wanted to include had to be cut, with no support available for those systems in the game engine.

If you didn't know DroidWorks was an educational game, you wouldn't have guessed it by today's standards. Kerbal Space Program is a fantastic spaceship building and spaceflight simulation, and despite not being considered an edutainment game, I like many others spent time learning and understanding real models of orbital mechanics as a necessity to get my little green friends to orbit and beyond. That's learning done good, and the same design is on display in DroidWorks.

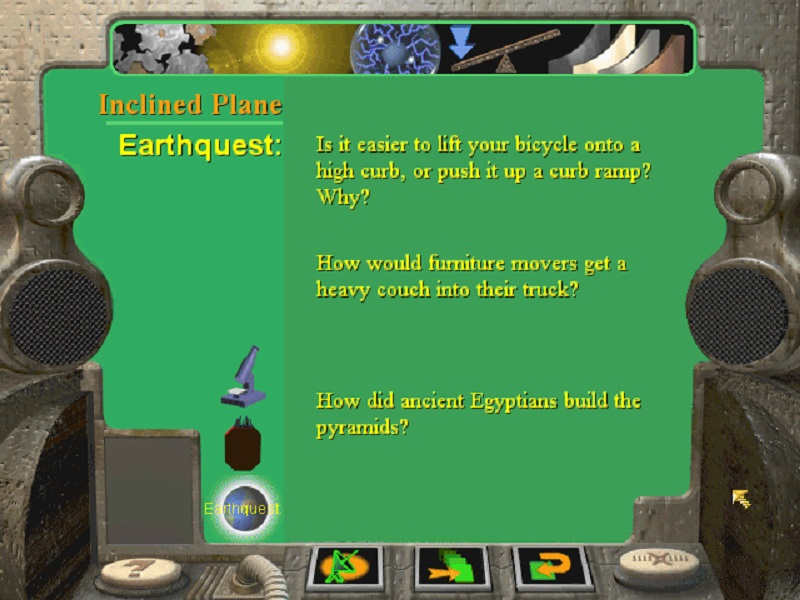

Each level select screen has a a link to a learning page with descriptions, pictures and animations to explain the real world concepts behind each level. It also provides everyday examples of the concepts in action that kids can more easily identify with. I didn't even know this existed when I was younger, it's there if you need or want it, but doesn't get in the way of the game at all. The puzzles are designed such that the player will learn intuitively by playing, backed up by the pages if they need a hint or want to learn more about it. It's edutainment done right.

The very first mission is a good example of this. Before you get to the puzzle you have to drive up an incline, which if you can't climb then you will have to go back to the drawing board, and might tip you off to what is required. The puzzle involves an incline that is too steep to climb up for any droid. A bit of curiosity and exploration will be able to find various buttons which move decreasingly steep inclines in front of the blockage. After a few of these you will hopefully reach one that your droid can manage to traverse and reach the end of the level.

It's simple, clearly shows the player what will be required, and the puzzle itself hints at what the solution would be and which concepts can be used to finish it. The developement team's goals for learning were self-directed and self-paced, to allow mistakes and trial and error so the player can experience that 'ah ha' moment and its achieved very successfully.

So what is it? The development team struggled from beginning to end on 'which shelf' DroidWorks belongs on: entertainment or education? This question was core to the design process and seems to have ebbed and flowed throughout development. Marketing was key and the question of who is buying this game, are children asking for it or are parents buying it for their kids' education? Michaud's answer is probably both. Lucas Learning used the Star Wars licence so that they would have an easier time selling it to brick and mortar stores but placing it, as it eventually landed, on the entertainment shelf "next to Quake" is a tough sell to consumers. DroidWorks is so much a game that I think this is the right place for it, but marketed to 10 and up, both boys and girls which was important from the beginning of development, the message is harder to get across than a pure action title marketed at 15-20 year old males. In her GDC talk, Michaud explains that even the other edutainment games of the time had bigger marketing budgets and tv adverts.

Once it was on the shelves, (regardless of which shelves) it recieved good reviews, many awards from educational institutions as well as a BAFTA, the first year the British Academy started awards for games. DroidWorks won the childrens category, alongside N64 Goldeneye 007 (1997) for the games category. It reportedly sold well, although not as commercially successful as the highly marketed brand names already mentioned in the same space with bigger budgets and more specific demographics.

To more clearly delineate themselves, Lucas Learning moved toward a younger age range, making it easier to specifically create and market the games. Their later games such as Star Wars: Yoda's Challenge - Activity Center (1999) and Star Wars: Early Learning Activity Center (2000) are marketing directly to the parents at a much younger age range, which also makes for simple educational goals to design and test for younger children compared to 3D physics problems.

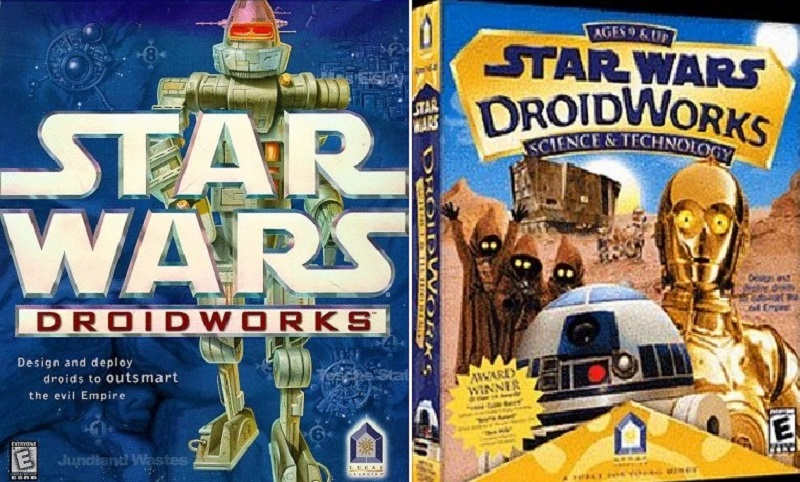

You can clearly see this from the original box art below on the left which is a game box like any other, and the updated box art on the right, clearly more targeted to children and learning.

The team were told by George Lucas to "make software that is as educational as it is entertaining, make it better than anything else on the market, and don't spend a lot of money." and I think they succeeded on all counts. It takes a visionary to take risks in areas like genuinely educational games for kids, when the easiest route is chasing the lowest common denominator for the broadest market and make the most cash possible. George Lucas obviously had a very strong desire to engage and teach children properly and looking back, by accident or not, Collette Michaud is obviously a huge factor of DroidWorks success.

Reading and listening about the game, Michaud's passion is obvious. She had worked on varied games at LucasArts such as Indiana Jones and then Fate of Atlantis and Rebel Assault, another curiousity that doesn't fit neatly into a genre box (she also worked on Sam and Max, where she met her husband creator of Sam and Max Steve Purcell!). If her dedication was in any doubt, she went on to become founder and CEO of the Children’s Museum of Sonoma County, a museum dedicated to interactive learning for children.

In a way I find it a shame that they veered into early learning as DroidWorks was such an interesting beast and yet another unusual 90s LucasArts curiosity, but it's obvious from a business point of view why it happened. They did pave the way for games not to be afraid of teaching or requiring players to learn some real world knowledge to succeed. KSP players wear their physics knowledge as a badge of pride, with endless guides and tutorials, real life physics lessons which can then be applied in game, a great motivator for interest in maths and science.

Edutainment is no longer a dirty word and an industry in which many successful freeform building games are teaching people new things is a great legacy for this game.