Lander

Acorn Archimedes, 1987

David Braben is most famous for co-creating wireframe space trading sim Elite, a legendary game then and now. His follow up game would have to be something incredible. It turned out to be a notoriously difficult graphical masterpiece with an interesting footnote in technology history.

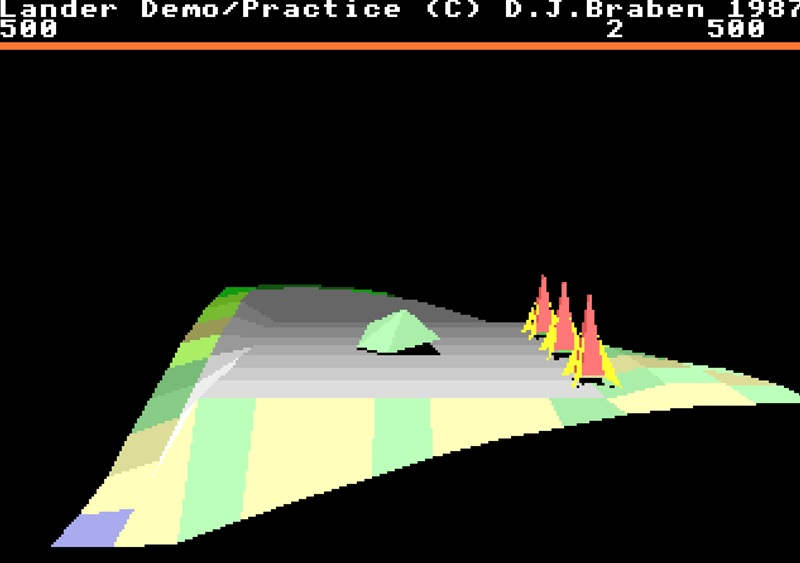

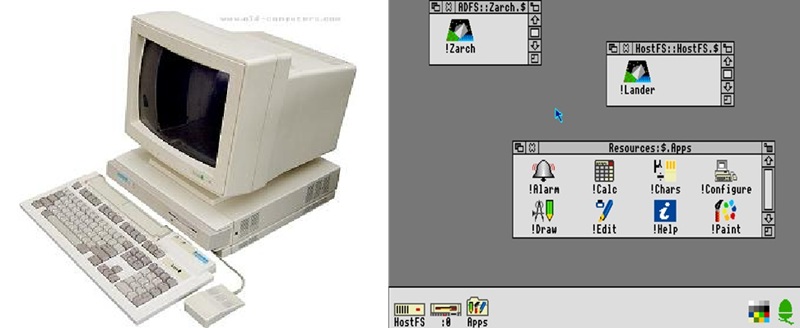

Despite this, his ‘difficult second album’ turned out not to be difficult at all, Braben knocking the demo out in two months. That demo was named Lander, commissioned by Acorn to be shipped on all their Archimedes computers, most of which were destined for classrooms across the country. While described as a demo, it was more of a proof of concept, but to thousands of 1980s British schoolchildren like me who didn’t know any better, it was a fully fledged game.

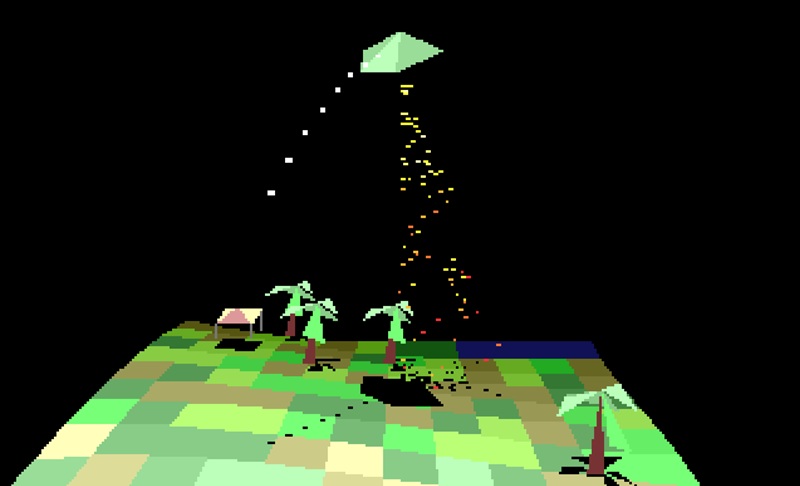

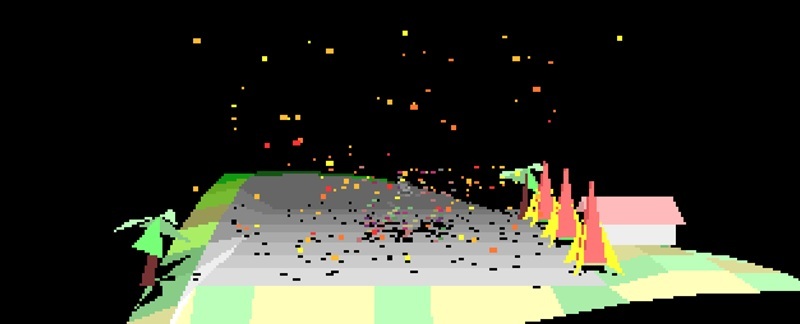

Whatever you call it, it was the first game ever released for the ARM processor, which as mentioned in my Stryker’s Run retrospective now powers almost all our computers and phones today. The processing power and specs of the Archimedes allowed one of the first 'filled polygon' games, as opposed to the wirferame look of games like Elite. A few had shown up in arcades by this time, and a home computer release I, Robot (Atari, 1984). It was amazing for the time and is still gorgeous, at least to my eyes. It's also a a lovely world, the dark sky contrasted with the trademark bright patchwork land. Rolling hills, sunny beaches with palm trees and blue ocean, even fish jumping out of the water. (Alright the fish are technically enemies but they don't hurt you and I will never hurt them. Fish gang 4 lyfe.)

The premise is simple. As many developers and publishers were to do in the decades to come, Braben simply took an old 2D game and reimagined it in 3D. This was most expertly done by one of my all time favourites Battlezone (Activision, 1998) although there were many others, mostly more straightforward conversions into the extra dimension. In this case the inspirations were the Lunar Lander genre and Defender (Williams, 1981), as well as Braben’s own unpublished Asteroids’ (Atari, 1979) clone.

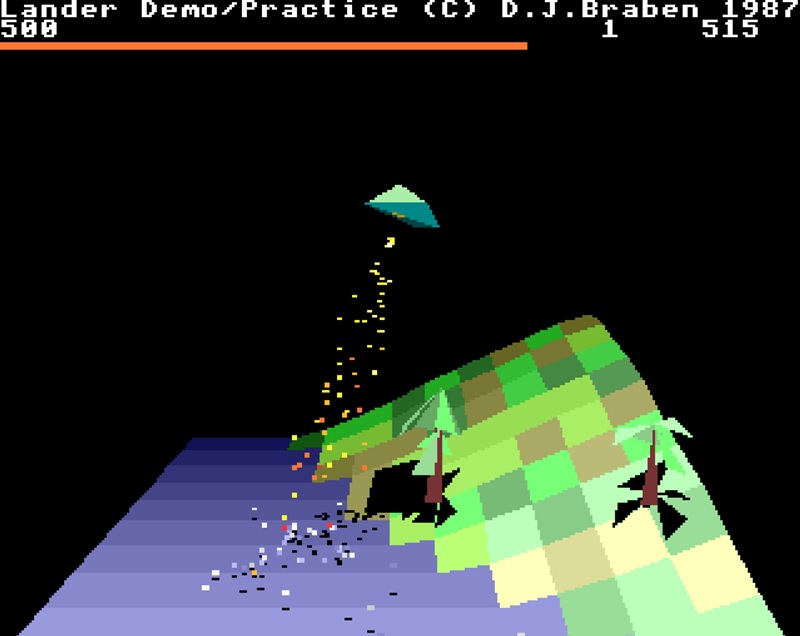

The particle effects are still so beautiful to me, every game I make as a hobby dev has them in, probably due to this game imprinting on me at a young age. Like in Tomb Raider, the limited draw distance and dark background gives an air of mystery and, at speed, adds a lot of tension as well.

Not that you need the extra tension; the controls are infamously difficult. It seems random at first, but you soon get the hang of it. The ship will pitch in whatever direction you move the mouse. To go right, move the mouse right and start firing your thruster as you would in Thrust (Jeremy C. Smith, 1986) or Lunar Lander (Atari, 1979). Move the mouse too far and you’ll turn upside down, usually still thrusting in the panic, firing yourself into the terrain at enormous speeds.

An interview by Andy Krouwel quotes Braben “It was so much dependent on how good your mouse was. In some cases [it was] virtually unplayable.” We lucky gamers in the 21st century can reduce their mouse sensitivity, which helps a huge amount. Short bursts of thrust and small mouse movements slow things down so that you can start to gain some control. Unlike Asteroids it's not Newtonian; there is a smidge of drag so when you accidentally fire yourself into the sky at warp speed (happens a lot) you will naturally slow down instead of accelerating forever.

Gameplay-wise there’s not much else to it. Hover around, shoot trees and buildings to get points. And that's it! And no one really bothered to shoot things anyway, we just were trying to survive, see more of the world, and do cool tricks without crashing. Even with so little in the way of objectives, none of the other games we had on the Acorns had the feeling of an actual world in there for you to discover.

Despite the simplicity, there are some simple and effective mechainics. You can refuel on the landing pad, but with no minimaap in the game, stray too far and you will lose your way home. It's extremly hard to land successfully anyway. Another twist is that each shot you fire reduces your score, but as it's so hard to aim, you must be precise.

Compounding this, as the targets are all on the ground requiring you to point down. A quick twitch of your finger may send you flying off in the direction you're facing (all too common). You have options here. You can propel yourself forward on a speedy strafing run, hoping to turn around and go back if you miss. Alternatively, cut thrust and float to the ground while firing, hoping you will be able to right yourself correctly and thrust before you crash.

It’s a thrilling trade off for the players choice or style, but you don't have to take my word for it, you can play it for yourself in the browser here!

Zarch

Acorn Archimedes, 1987

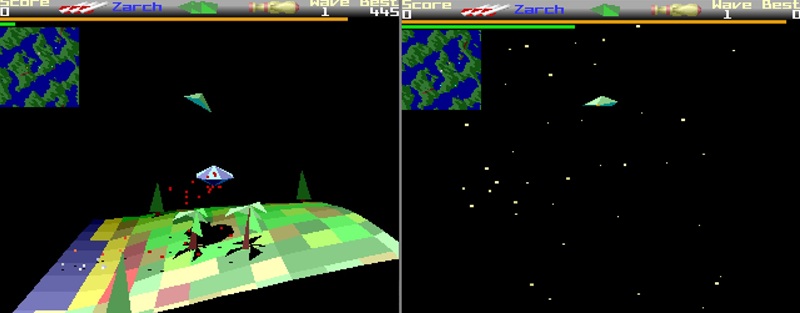

Lander was soon fleshed out into a full game. The basics remained the same, but now enemy spaceships are seeding a virus on the terrain, turning it red. You must kill them before they cover the map (now represented with a minimap), and destroy any of their support craft that come to attack you. You also have a limited number of bombs and homing missiles to deal with these advanced threats.

There are some other surprisingly deep systems at play, for what is still an arcade shooter. There are radar towers across the map that, if destroyed, will black out parts of the minimap. That means you wont be able to see the enemies and hunt them down, or see which areas of the map are infected. Meanwhile some of the infected buildings and plants may mutate, which in turn allows enemies to also mutate and change behaviour.

Some of these advanced enemies are almost impossible to kill without these special weapons and some of them will even kamikaze at you at high speed. Once you’ve cleared the map of enemies, you get a bonus score based on how much of the map was converted to virus, how many kills you had and so on, and move on to the next level. It’s more involved, but doesn’t add too much challenge to a game where just battling gravity and your mousepad is already the lion's share of the challenge.

It’s still as absolutely brutal as any of the games of that era. In fact, the demo mode shown when you boot up the game shows the computer control of the ship, which Braben notes in an interview easily out-performed human players, despite being a few rudimentary lines of code. Indeed, watching it will make you jealous. It also has a bit of the good old British sense of humour, with various messages mocking you for being bad at the game.

“Because of the way the mouse control works the tendency is to shoot downwards.”, Braben explains. “You end up in a war of height against the bad guys. Inevitably you end up leaving the ground behind”. “We appreciated that fairly early on, which was one of the reasons we made sure that the Seeders land. You have to come quite low to shoot them”

With the added systems and details it looks even more fantastic and is a lot more engaging than the barebones Lander. It's still eminently playable despite, or perhaps because of, its difficulty. It's this version that is definitive, but it was ported to other systems under the name Virus

Virus

Amiga, Atari ST, DOS, ZX Spectrum, 1987

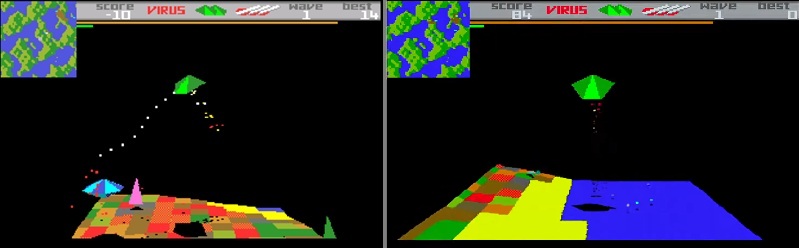

Most of these ports included keyboard controls, which is a blessing and a curse. It's easier to play, but it's a keyboard mapping of the existing control scheme. A ground-up keyboard system would have made more sense and felt more intuitive. On the other hand, while it's easier to stay alive, the slower pace means it's much harder to aim and shoot at anything, let alone moving targets. It turns into a twitch shooter without the twitching.

The Acorn version remains the best, but the Amiga version is closest to it, and the Amiga was much more common in households than the expensive Archimedes. The Atari ST version is also similar enough, but much slower. It's still slightly better than tha terrible DOS version.

The DOS version's graphics are much worse, with blander colours and sad sound effects. Its most notable attribute is having been coded by Chris Sawyer, he of Rollercoaster/Railway Tycoon fame. It’s funny that at the time among shoolfriends, Acorn was seen as the poor and boring cousin of PCs. Of course that bore out eventually, but in terms of capability it was streets ahead as this port shows.

The ZX Spectrum port is also playable online, but you won’t want to. It’s like when an N64 game got a GBA port, basically a different game. It’s very slow, barely playable and lacks the tradmark filled polygons that made it stand out. Although it was impressive for this aging system at the end of its lifespan, it was probably best not to have made it. The publisher agreed and had not commissioned it, but a bedroom coder Steven Dunn sent a completed a demo of it which was approved.

None of these are worthy of the original, but the Amiga port is the next best thing. What the ports did mean though, is that Zarch reached a much bigger audience than the nerdiest strata of 1980s British schoolchildren, and while it could never reach the lofty heights of Elite, it does have its modest place in history.

Zarch spawned a very different sequel, Conqueror (Jonathan Griffiths, 1988), with which Braben was not involved, as well as a more modern sequel V2000 (Frontier, 1999). Despite being lesser known today, one could (and in future articles I will!) argue Zarch inspired a modest sub-genre, with influences reaching into the next couple of decades.